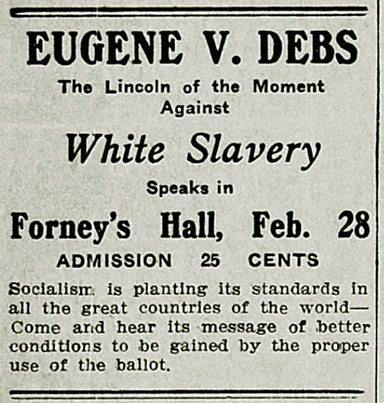

As we have seen, Gene Debs was very close to those who organized the Industrial Workers of the World but took a rather casual approach to the new industrial union, delivering a speech at the founding convention before departing to deliver paid lectures, then speaking under its auspices about eight times during the fall of 1905. (See: Debs Blog 19-03: “Near It But Not In It”)

He did not attend the second IWW convention, held in 1906, at which the organization blew apart in a factional squabble, and scarcely mentioned the group again, nor did he write for either of the competing factions during the latter part of 1906 and all of 1907. (See: Debs Blog 19-09: “The IWW Split of 1906”) Without making public acknowledgment of such, he had sadly washed his hands of it and was done; just as his political nemesis on the left, Daniel DeLeon, by way of contrast, dug in and scrapped for the empty husk of an organization which remained.

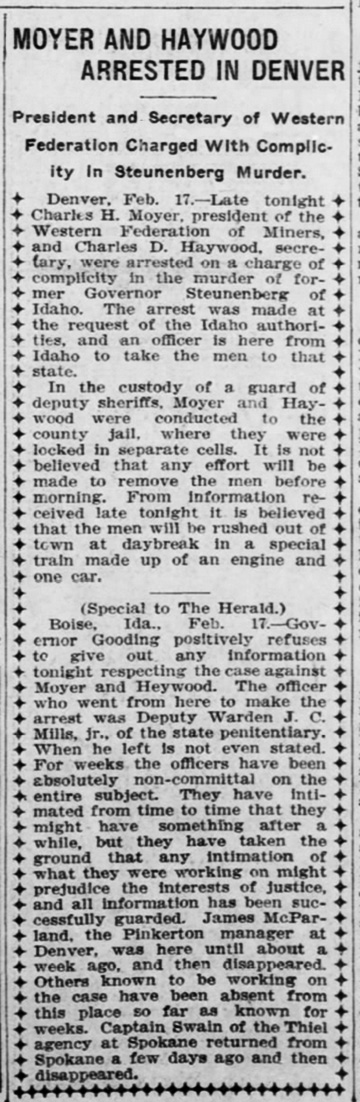

Instead, Debs became preoccupied — some might say “fixated,” but preoccupied is a better term — with the attempt of western mine owners and the political establishment of the mining states of Colorado and Idaho to decapitate and destroy the militant socialist Western Federation of Miners by implicating their president, Charles Moyer, and secretary-treasurer, Big Bill Haywood, in the Dec. 30, 1905 assassination by bombing of former Idaho Governor Frank Steuneberg outside his home in Caldwell, Idaho. (See: Debs Blog 19-08: “Debs and the Haywood-Moyer Affair of 1906”)

Moyer and Haywood, along with a former member of the WFM board, George Pettibone, had been secretly arrested in Denver and hustled out of state aboard a special train under the cover of darkness on a weekend, a brazen attempt to skirt extradition law so that they might be tried in Idaho for conspiracy to commit murder — a capital offense.

Debs transformed himself from touring professional lecturer to well-paid journalist on the staff of the blossoming Appeal to Reason, leaving his wife in Terre Haute and taking up residence near the publication’s offices in small town of Girard, Kansas. (See: Debs Blog 19-11: “From Long Speeches to Long Articles”) He wrote copiously and in the most impassioned terms in defense of the Western Federation of Miners leaders, attracting helpful public attention to the case but drawing fire from conservative commentators, up to and including the president of the United States, Theodore Roosevelt, who made public a letter in which he referred to Debs, Moyer and Haywood as “undesirable citizens.” (See: Debs Blog 19-12, “Undesirable Citizens”)

We come now to the sensational trial of Big Bill Haywood.

• • • • •

The Venue

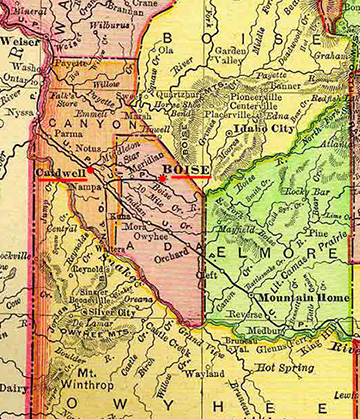

Proximity of Caldwell (site of the Steunenberg murder) and Boise (site of the Haywood trial) in Southwestern Idaho. The vicinity is flat and agricultural, not mining country.

The three WFM defendants were to be tried separately rather than collectively. A change of venue was granted to the defense, moving the trial from the small, insular town of Caldwell, located in rural Canyon County, to Idaho’s capital city, Boise, located about 25 miles away in more populous Ada County. The significant costs of the investigation and trial were ultimately absorbed by the state through decision of the state legislature.

A legal team had rapidly been assembled to defend the arrested union leaders, with Western Federation of Miners attorney E.F. Richardson arriving in Boise from Denver on February 20, 1906, immediately after the special train, where he initiated habeas corpus proceedings, in which he charged that the procedure used to move Moyer, Haywood, and Pettibone had been illegal and the warrants under which they were arrested defective.

The matter was argued in court early in March, with the state successfully moving to strike all references to the manner of extradition and allusions to conspiracy of state officials against the WFM leaders from the case, a decision rendered by the Idaho Supreme Court on March 12. (fn. David H. Grover, Debaters and Dynamiters: The Story of the Haywood Trial. Corvallis, OR: Oregon State University Press, 1964; pp. 71-72.)

Richardson prepared a bill of exceptions, signed by the Idaho Supreme Court, which effectively moved jurisdiction of the appeal from state to federal court. On March 15 he filed new writs of habeas corpus with the US Circuit Court of Boise, with Judge James H. Beatty on the bench. The matter was argued in court for four days with a similar result, Beatty ruling that the court lacked the power to investigate the means of extradition once the prisoners were in legal custody of the state of Idaho. (fn. Grover, Debaters and Dynamiters, p. 72.)

From there another appeal was made, this time to the United States Supreme Court based on a writ of error, with a test case, Pettibone v. Nichols, accepted by the court for its October 1906 docket. (fn. Grover, Debaters and Dynamiters, p. 72.)

• • • • •

The Prosecution and Defense Teams

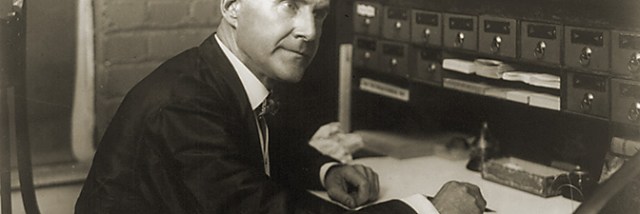

James H. Hawley (1847-1929) was a prominent attorney and major political figure in Idaho, brought aboard to lead the prosecution in the Haywood conspiracy-to-commit-murder case.

In the meantime, defense funds were raised and legal teams built, including James H. Hawley, a former mayor of Boise and future governor of Idaho, and soon-to-be US Senator William E. Borah for the prosecution, and nationally renowned attorney Clarence Darrow, a silver-tongued advocate for the downtrodden, joining Richardson for the defense. These would be the four main attorneys in the contest, meeting in court for the first time on October 10 before the US Supreme Court to argue the Pettibone habeas corpus case appeal.

The Supreme Court ruled in favor of the state, 7-1 (there was one vacancy), with Justice John M. Harlan writing the opinion for the majority. Harlan wrote that the Governor of Colorado was responsible for determining whether Pettibone (and the other defendants) was actually a fugitive from justice, but that he was not under obligation to demand proof of the same in connection with the requisition order, and that this deficiency was not an infringement of Pettibone’s rights under the US Constitution. He also held that, critically:

Even were it conceded, for the purposes of this case, that the governor of Idaho wrongfully issued his requisition, and that the governor of Colorado erred in honoring it and issuing his warrant of arrest, the vital fact remains that Pettibone is held by Idaho in actual custody for trial under an indictment charging him with crime against its laws, and he seeks the aid of the circuit court to relieve him from custody, so that he may leave the state and thereby defeat the prosecution against him without trial. (fn. Quoted in Grover, Debaters and Dynamiters, p. 72.)

Thus, possession of the defendants was 9/10ths of the law, so to speak. The method of arrest, detainment, and transfer across state lines was not a matter which would be allowed to determine the defendants’ fate in the matter at hand.

• • • • •

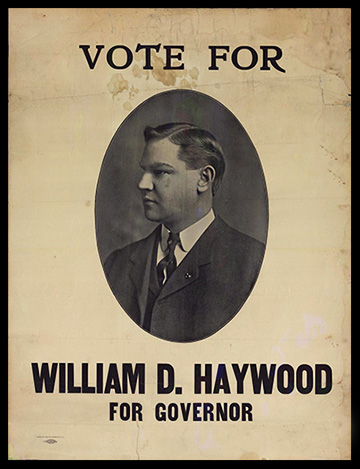

Big Bill Haywood

William Haywood, Jr. was a child of the American West, born in February 1869 in Salt Lake City to a young, non-Mormon couple. His father, a miner, died of pneumonia in 1872, leaving young Bill’s 18-year old mother to raise him alone for the next several years, before she remarried, again to a miner. The family moved to the mining camp at Orphir, located in the Oquirrh Mountains, where Bill spent several of his boyhood years. He took his first job in Orphir, probably working as a breaker boy, when he was just 9 years old. (fn. Joseph R. Conlin, Big Bill Haywood and the Radical Union Movement. Syracuse, NY: Syracuse University Press, 1969; pp. 2-3.)

The family eventually returned to Salt Lake City, where Bill was hired out as a general laborer for a local farmer, earning a dollar a month. He also worked variously as a wood-chopper, hotel porter, and messenger boy. His stepfather eventually became the manager of a mine and milling company in Humboldt County, Utah, and when Bill was 15 he moved away from home to take a job there. (fn. Conlin, Big Bill Haywood, op cit., p. 5.)

Haywood would remain in his stepfather’s employ for three years, even staying to work as a property guard when the mine ceased operations for financial reasons in 1887.

In the words of one of his biographers, the historian Joseph R. Conlin:

The fact is that Bill Haywood got along quite well in Salt Lake City and Orphir, and remembered his childhood fondly and in some detail; this revolutionary’s alienation did not begin in Zion. * * *

He was intelligent, full of curiosity, and ambitious. His formal education was negligible; he had only a few years of schooling in Orphir and at a Roman Catholic school in Salt Lake City. But Haywood had exploited Salt Lake City’s relatively broad cultural offerings and became ‘an ardent reader of Shakespeare’ as well as a passably competent chess player… Haywood’s stepfather was a lover of poetry and introduced young Bill to Voltaire, Byron, Burns, and Milton. Haywood showed a keen interest in learning about virtually anything new with which he came into contact…. He was intrigued by everything from prehistoric mastodon tracks to Indian dances, and remained open-minded and curious throughout his life. (fn. Conlin, Big Bill Haywood, op cit., pp. 5-7.)

In 1887 Haywood took another mining job, working this time as a fireman and engineer on the small train which carried ore and waste rock to the surface of the Brooklyn Mine, located near Salt Lake City. He married in 1889 and determined to leave underground employment, attempting to make a living briefly and unsuccessfully as a metal assayer and a gold prospector. He would leave the mining business altogether in 1890, when he took a job as a hand for a cattle rancher before eventually returning to the mines. (fn. Conlin, Big Bill Haywood, op cit., pp. 7-8.)

In 1887 Haywood took another mining job, working this time as a fireman and engineer on the small train which carried ore and waste rock to the surface of the Brooklyn Mine, located near Salt Lake City. He married in 1889 and determined to leave underground employment, attempting to make a living briefly and unsuccessfully as a metal assayer and a gold prospector. He would leave the mining business altogether in 1890, when he took a job as a hand for a cattle rancher before eventually returning to the mines. (fn. Conlin, Big Bill Haywood, op cit., pp. 7-8.)

Haywood briefly homesteaded at Fort McDermitt, a brief interlude at domesticity which was ultimately defeated by his wife’s chronic ill health and the lack of gainful employment in close proximity to his home. (fn. Conlin, Big Bill Haywood, op cit., pp. 8-9.)

In the depression year of 1894, Haywood left his ailing wife and daughter with his in-laws and made his way to Silver City, Idaho to attempt to find a mining job there. The job situation was grim, with Haywood forced to start as a car man, shoveling rock at the Blaine Mine. He was eventually able to find a more remunerative position as a miner in the same mine and sent for his wife and daughter to join him — with a second daughter added to the family shortly after the pair arrived.(fn. Conlin, Big Bill Haywood, op cit., p. 20.)

In June 1896, Haywood suffered a serious hand injury while riding a car back to the surface of the Blaine Mine. He was unable to work while recovering. Towards the middle of August, President Ed Boyce of the Western Federation of Miners visited the Blaine Mine attempting to organize it. Haywood was inspired and joined the union, soon becoming treasurer of the new local. He attended meetings regularly and gained a reputation for keeping honest and accurate accounts. (fn. Conlin, Big Bill Haywood, op cit., pp. 20-21.)

Haywood was tapped by the Silver City local as its delegate to the 1898 annual convention of the WFM, held in Salt Lake City. There he was named to the executive board of the Western Labor Union, the WFM’s federative body which attempted to bring non-mining workers into organized cooperation with the WFM. From that date he also began to make a national name for himself as a contributor of articles to Miners’ Magazine, the official organ of the WFM. Boyce returned to Silver City after the 1898 convention and embarked on a short organizing trip to the neighboring town of Delmar with Haywood in tow. (fn. Conlin, Big Bill Haywood, op cit., p. 21.)

Haywood was returned as a delegate to the 1899 convention of the WFM, where as a Boyce protege he was elected to the executive board of the organization. Haywood attended board meetings at Butte and became involved as a liaison between the central union and its militant Coeur d’Alene affiliate. The job as a union functionary was only part time, however, and it was not until the following year that Haywood was made a permanent employee of the union. (fn. Conlin, Big Bill Haywood, op cit., pp. 21-22.)

• • • • •

The Jury

As this was a high-profile, costly, high-stakes capital trial, both the prosecution and the defense made earnest efforts to skew the jury for their own benefit. For weeks before the trial both teams made door-to-door canvasses throughout Ada County attempting to determine the specific inclinations and biases of prospective jurors. In yet another example of dirty tricksterism, the prosecution managed to infiltrate a Pinkerton agent, code-named “Operative 21,” into the defense’s canvas team. This agent supplied long lists of those interviewed by the defense along with their ratings — “OK for defense” or “NG for defense.” (fn. Grover, Debaters and Dynamiters, p. 72.)

At least half of the dozen men ultimately seated on the jury had been interviewed and rated by the defense, with information funneled by the Pinkerton spy to the prosecution. However jury analysis was clearly an inexact science; four of these six had been rated as “No Good for defense,” were seated, but ultimately voted for acquittal; while two seated after being rated “OK” ultimately voted to convict, leading one historian to voice the highly unlikely proposition that perhaps the prosecution’s infiltrator had been played by a cognizant defense. (fn. Grover, Debaters and Dynamiters, p. 72.)

Jury selection was finally completed on June 3, 1907. The jury included nine farmers and ranchers (one now retired), a real estate agent, an unemployed former carpenter and farmer, and an ex-farmer now employed as a fence-builder for a local railway. Only one had ever been a member of a trade union, and that had been a number of years before. The jurors were almost exclusively middle-aged and older. Politically, these were eight Republicans, three Democrats, and a Prohibitionist — seemingly a fine set of material for the prosecution. (fn. Grover, Debaters and Dynamiters, pp. 101-104.)

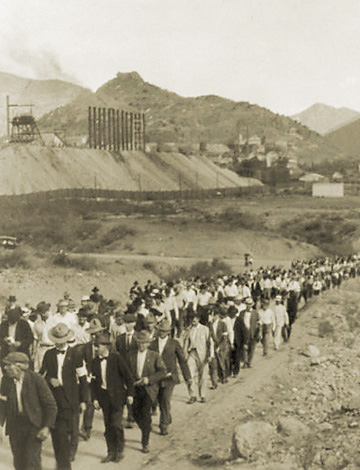

A seven-week trial followed, with the eyes of the nation focused upon the proceedings. The correspondents of an estimated 50 magazines and newspapers converged upon Boise, then a town of about 15,000 residents, to deliver blow-by-blow accounts to readers around the nation. (fn. Grover, Debaters and Dynamiters, pp. 105, 107.)

• • • • •

Harry Orchard’s Story

Albert E. Horsley (aka Harry Orchard, 1866-1954), confessed terrorist and assassin, who eventually lived out his life in the Idaho State Penitentiary after his death sentence was commuted.

The state began its case against Bill Haywood on the morning of June 4, 1907, with James H. Hawley making a 90-minute opening statement for the prosecution. Hawley emphasized the power of the Executive Committee of the WFM in determining the day-to-day affairs of the union, and argued that the policies advocated by the union leadership had led to the death of former Governor Steunenberg and others. Clarence Darrow, for the defense, crossed swords with Hawley a number of times with procedural objections during the opening statement, the start of what would be a bitter and antagonistic relationship. (fn. Grover, Debaters and Dynamiters, pp. 114-116.)

The state quickly established that Harry Orchard and member of the WFM board Jack Simpkins had been in Caldwell several times during the fall of 1905, rooming together under the pseudonyms Hogan and Simmons, with photographs of the pair identified by witnesses. (fn. Grover, Debaters and Dynamiters, p. 117.)

With that background established, the prosecution called Harry Orchard to the stand, where he acknowledged that his real name was Albert E. Horsley, born in Ontario, Canada 41 years previously. Horsley-Orchard briefly described his early work career, culminating in his arrival at Cripple Creek, Colorado, in 1902, and his connection with the explosion at the Vindicator Mine. (fn. Grover, Debaters and Dynamiters, p. 119.)

Horsley-Orchard stated that he had gone to Denver after the Vindicator bombing and met WFM officials Charles Moyer and Bill Haywood for the first time, where he asserts he was told to continue with other acts of violence which “couldn’t go any too fierce to suit them.” Horsley-Orchard states he was paid $300 by the WFM leaders and then returned to Cripple Creek, where he built a bomb which was later placed in the coal bunker of the Vindicator Mine. (fn. Grover, Debaters and Dynamiters, p. 119.)

Horsley-Orchard then said he worked as a bodyguard for Moyer until his arrest at Telluride, after which he returned to Denver and was instructed by Haywood and George Pettibone of the WFM to kill Governor Peabody of Colorado for his actions taken against the striking miners, with Steve Adams recommended to help Horsley-Orchard carry out the assassination. The pair attempted to shadow Peabody but were unable to get close enough to carry out the killing, Horsley-Orchard asserted. (fn. Grover, Debaters and Dynamiters, p. 119.)

Horsley-Orchard says he next carried out the assassination of detective Lyte Gregory in Denver in the spring of 1904, with Pettibone placing the hit on behalf of the WFM executive. Horsley-Orchard and Adams were each paid $100 for their part in the late-night shooting, he claimed. (fn. Grover, Debaters and Dynamiters, p. 119.)

The June 6, 1904, bombing of the depot at Independence, Colorado was the next act of violence claimed by Horsley-Orchard, in which he claimed that he and Steve Adams had placed a dynamite bomb under a train station platform and detonated it with a 200-foot wire as strikebreaking miners congregated to board a train home after a day’s work. Thirteen were killed and six wounded in the blast. Horsley-Orchard indicated that he had hid out in Wyoming after the bombing, collecting money from Haywood for services rendered. (fn. Grover, Debaters and Dynamiters, p. 120.)

Next, Horsley-Orchard had traveled to California to assassinate Fred Bradley of the Mine Owners’ Association, failing in an attempt to poison him before wounding him with a bomb. Another plot to kill Peabody was made, this time with a bomb, was alleged to have been made, but the effort was said to have been halted at the last minute due to the unexpected appearance of potential witnesses. A tale of various other assassination plots was recounted with Colorado Supreme Court justices Gabbert and Goddard and Colorado Adjutant-General Sherman Bell said to be among the potential victims who escaped a violent end. (fn. Grover, Debaters and Dynamiters, p. 120.)

It was then that Horsley-Orchard says he was dispatched to Caldwell, Idaho to kill Frank Steunenberg, meeting his accomplice Jack Simpkins before proceeding to Idaho. A first attempt to kill the governor with a bomb had failed, Horsley-Orchard declared, and Simpkins had left town before the second effort to kill Steunenberg with an explosive device had yielded results. (fn. Grover, Debaters and Dynamiters, p. 121.)

A 26-hour cross-examination followed, with attorney Edmund F. Richardson attempting to impeach Horsley-Orchard’s story without much apparent success.

[… to be continued …]

The official deadline for Eugene V. Debs Selected Works: Volume 4 is October 15, 2019. I’m setting a soft deadline of August 1 to finish the document compilation phase of the project. This means there are now 11 more Sundays after today to get the core content section of the book assembled, with a limit for publication of approximately 260,000 words.

- “Growth of the Injunction” (May 6, 1905) — 1,986 words

- “For the First Time Our Comrades Are Safe: Letter to James Kirwan, Acting Secretary-Treasurer of the Western Federation of Miners” (March 2, 1907) — 338 words

- “Looking Backward: Thirty Years of Struggle for Labor Emancipation” (Nov. 11 1907) — 1,877 words

- “John Brown, History’s Greatest Hero” (Nov. 23, 1907) — 873 words

- “Thomas McGrady: Eulogy to an Honest Man” (Dec. 14, 1907) — 2,124 words

- “Childhood” (Dec. 21, 1907) — 359 words

- “Panic Philosophy” (Dec. 28, 1908) — 376 words

Word count: 168,087 in the can + 7,933 this week +/- amendments = 175,705 words total.

David Walters will be running all of this material up on Marxists Internet Archive in coming days.

To find it, please visit the Eugene V. Debs Internet Archive

Here’s the microfilm that I’ve scanned this week, available for free download. Bear in mind that there is generally a short delay between completion of the scanning and its appearance on MIA. Thanks are due to David Walters for getting this material into an accessible format.

Several hundred issues of two of the Socialist Party’s three English-language daily newspapers have been completed.

• New York Call — 1908 (Nov.-Dec.), 1909 (Jan.-Feb.)

• Chicago Daily Socialist — 1908 (Jan.-June)

I also worked a reel of the Debs papers film for the second half of 1908, which netted a copy of the October 5, 1908 issue of the New York Call, effectively lost through incompetent microfilming, that I groused about in last week’s blog as well as a number of other rare socialist newspapers.

Haymarket Books is moving down the back stretch with Volume 2: The Rise and Fall of the American Railway Union, as David and I were officially invited to submit indexing suggestions to a proofread copy.

The book is slated for release in August 2019.

Volume 4: Red Union, Red Paper, Red Train, 1905-1910 is progressing swimmingly. There are nearly 170,000 words in the can, which probably projects to something like 310,000 when the smoke clears. David and I will need to cut down to 260,000. That’s just about a perfect situation when we go into the work of diamond cutting.

Volume 4: Red Union, Red Paper, Red Train, 1905-1910 is progressing swimmingly. There are nearly 170,000 words in the can, which probably projects to something like 310,000 when the smoke clears. David and I will need to cut down to 260,000. That’s just about a perfect situation when we go into the work of diamond cutting.

The term “undesirable citizen” did not originate with Theodore Roosevelt. In fact, the exact phrase begins to pop up in American newspapers in the years immediately after the American Civil War. In its first iteration, “undesirable citizen” was a Gilded Age term mockingly employed by defenders of polite society from the aggressions and transgressions of the most brazen ne’erdowells of the lumpenproletariat.

The term “undesirable citizen” did not originate with Theodore Roosevelt. In fact, the exact phrase begins to pop up in American newspapers in the years immediately after the American Civil War. In its first iteration, “undesirable citizen” was a Gilded Age term mockingly employed by defenders of polite society from the aggressions and transgressions of the most brazen ne’erdowells of the lumpenproletariat. With the marked expansion of immigration to the United States in last two decades of the nineteenth century, we find use of the phrase “undesirable citizen” shifting from erudite editorialists bemoaning criminal thugs to the customs and immigration bureaucracy and non-governmental opponents of foreign immigration. The term was now used to describe potential naturalization candidates destined to fail the winnowing process — particularly those not “white” enough.

With the marked expansion of immigration to the United States in last two decades of the nineteenth century, we find use of the phrase “undesirable citizen” shifting from erudite editorialists bemoaning criminal thugs to the customs and immigration bureaucracy and non-governmental opponents of foreign immigration. The term was now used to describe potential naturalization candidates destined to fail the winnowing process — particularly those not “white” enough. Applicability of the term “undesirable citizen” was further extended to cover strikers and strike leaders during the days of the so-called Citizens’ Alliances around the turn of the 20th Century. The former association of the term with a need to stop a stream of alien outsiders from entering and disrupting the fabric of the nation was supplanted by a new emphasis on those disrupting the divine right of profits of American “captains of industry,” thereby undermining the national economy.

Applicability of the term “undesirable citizen” was further extended to cover strikers and strike leaders during the days of the so-called Citizens’ Alliances around the turn of the 20th Century. The former association of the term with a need to stop a stream of alien outsiders from entering and disrupting the fabric of the nation was supplanted by a new emphasis on those disrupting the divine right of profits of American “captains of industry,” thereby undermining the national economy. So we see that when he made use of the term “undesirable citizens” in 1906 and 1907, President Theodore Roosevelt was merely echoing a popular phrase which had evolved and become part of the vocabulary of contemporary conservatism — a phrase used directly in the context of labor disruption.

So we see that when he made use of the term “undesirable citizens” in 1906 and 1907, President Theodore Roosevelt was merely echoing a popular phrase which had evolved and become part of the vocabulary of contemporary conservatism — a phrase used directly in the context of labor disruption.

• A more serious Debs biographer, Ball State history professor Floy Ruth Painter, in his slim 1929 volume, That Man Debs and His Life Work, fanned on the matter of a 1907 Debs life change completely:

• A more serious Debs biographer, Ball State history professor Floy Ruth Painter, in his slim 1929 volume, That Man Debs and His Life Work, fanned on the matter of a 1907 Debs life change completely: Early in January of 1907, he wrote to J.A. Wayland

Early in January of 1907, he wrote to J.A. Wayland • Indiana State University speech professor Bernard J. Brommel published a book in 1978 that I include in the small set of serious historical biographies of Gene Debs. His Eugene V. Debs: Spokesman for Labor and Socialism, quaintly, was published in Chicago by the Charles H. Kerr Publishing Co., a 90-year old imprint coming out of a deep sleep under new ownership after nearly fading into oblivion as the publishing arm of the tiny Proletarian Party of America.

• Indiana State University speech professor Bernard J. Brommel published a book in 1978 that I include in the small set of serious historical biographies of Gene Debs. His Eugene V. Debs: Spokesman for Labor and Socialism, quaintly, was published in Chicago by the Charles H. Kerr Publishing Co., a 90-year old imprint coming out of a deep sleep under new ownership after nearly fading into oblivion as the publishing arm of the tiny Proletarian Party of America. • For my money the best biography of EVD is that by Cornell professor Nick Salvatore, Eugene V. Debs: Citizen and Socialist, published by the University of Illinois Press in 1982. I don’t usually write in books, but I’ve marked up my first copy so severely with agreements and disagreements and asterisks to mark content that I had to buy another for my shelf. If my introductions are a dialog with any other historian, they are with Salvatore.

• For my money the best biography of EVD is that by Cornell professor Nick Salvatore, Eugene V. Debs: Citizen and Socialist, published by the University of Illinois Press in 1982. I don’t usually write in books, but I’ve marked up my first copy so severely with agreements and disagreements and asterisks to mark content that I had to buy another for my shelf. If my introductions are a dialog with any other historian, they are with Salvatore. • In the 1983 introduction to the large format paperback The Papers of Eugene V. Debs, 1834-1945: A Guide for the Microfilm Edition, J. Robert Constantine marks the move to the Appeal but seems to obviously undersell the magnitude of the new situation:

• In the 1983 introduction to the large format paperback The Papers of Eugene V. Debs, 1834-1945: A Guide for the Microfilm Edition, J. Robert Constantine marks the move to the Appeal but seems to obviously undersell the magnitude of the new situation:

As we have seen, after Gene Debs left his position as secretary-treasurer and magazine editor of the Brotherhood of Locomotive Firemen he made his living — a comfortable, middle class living — as a professional orator.

As we have seen, after Gene Debs left his position as secretary-treasurer and magazine editor of the Brotherhood of Locomotive Firemen he made his living — a comfortable, middle class living — as a professional orator. It should also be mentioned here that Debs was also — simultaneously and independently — a political opinion writer and commentator on public events. He was not a theoretician, but rather an analyst of issues and events who sought to inspire and motivate. This work he did pro bono, at least through 1906. His audience for the written word, generally speaking, was not the general public but rather fellow believers in the socialist cause.

It should also be mentioned here that Debs was also — simultaneously and independently — a political opinion writer and commentator on public events. He was not a theoretician, but rather an analyst of issues and events who sought to inspire and motivate. This work he did pro bono, at least through 1906. His audience for the written word, generally speaking, was not the general public but rather fellow believers in the socialist cause.

A June 15 appearance at a WFM defense mass meeting in Toledo, Ohio was made, where Debs spoke before a crowd of 1,200. A handful of Midwestern dates followed, including Horton, Kansas (June 19) and South Omaha (June 22).

A June 15 appearance at a WFM defense mass meeting in Toledo, Ohio was made, where Debs spoke before a crowd of 1,200. A handful of Midwestern dates followed, including Horton, Kansas (June 19) and South Omaha (June 22). Contrary to the telling in volume 4 of Philip Foner’s factually sloppy History of the Labor Movement in the United States, Debs spoke very infrequently in 1905 and 1906 under IWW auspices — three times in Chicago and five times in New York in 1905, the apparent frequency of which was dramatically exaggerated by the presence of a stenographer and conversion of four of these eight speeches into published pamphlets. (See:

Contrary to the telling in volume 4 of Philip Foner’s factually sloppy History of the Labor Movement in the United States, Debs spoke very infrequently in 1905 and 1906 under IWW auspices — three times in Chicago and five times in New York in 1905, the apparent frequency of which was dramatically exaggerated by the presence of a stenographer and conversion of four of these eight speeches into published pamphlets. (See:  Throughout his life, Debs retained a mystical belief in the power of elections to overthrow capitalism and install a fundamentally new order. The patently obvious reality that elected Socialist politicians were able to only do their best to attenuate the worst excesses of the system through ameliorative reform did not dampen his enthusiasm in the slightest.

Throughout his life, Debs retained a mystical belief in the power of elections to overthrow capitalism and install a fundamentally new order. The patently obvious reality that elected Socialist politicians were able to only do their best to attenuate the worst excesses of the system through ameliorative reform did not dampen his enthusiasm in the slightest.